On a secluded beach at the end of Ravine Drive in Highland Park now sits a rock garden that has (I hope) a little bit of mystery and magic in it.

Ravine Drive is a winding road, secluded, lush with old trees and elegant houses. A small parking lot laid at the end marks the entrance to Millard Park and Ravine Drive Beach.

The beach has undergone a significant transformation over the past year. An old building was torn down, its foundation ripped out of the sand. Native foliage was replanted. And a lifelong resident of Highland Park’s curiosity and fascination with the stones that wash up on shore was brought to life.

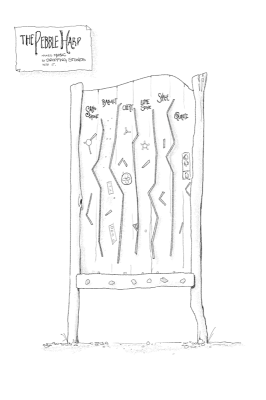

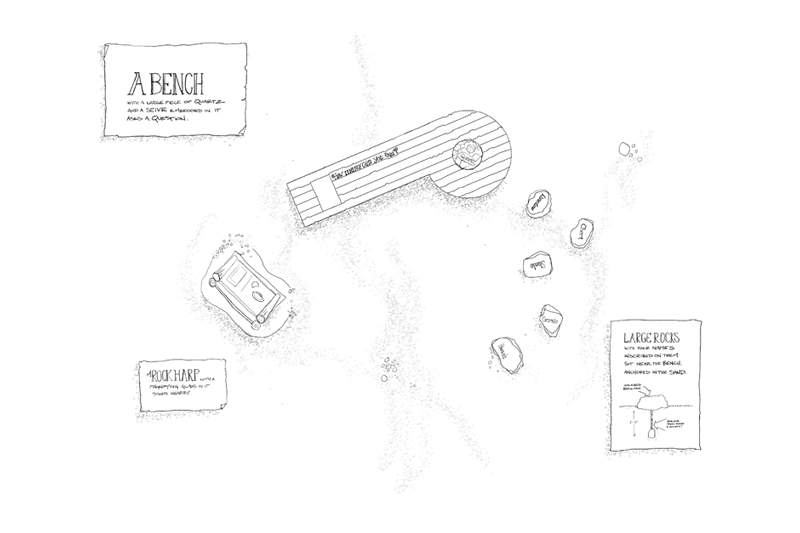

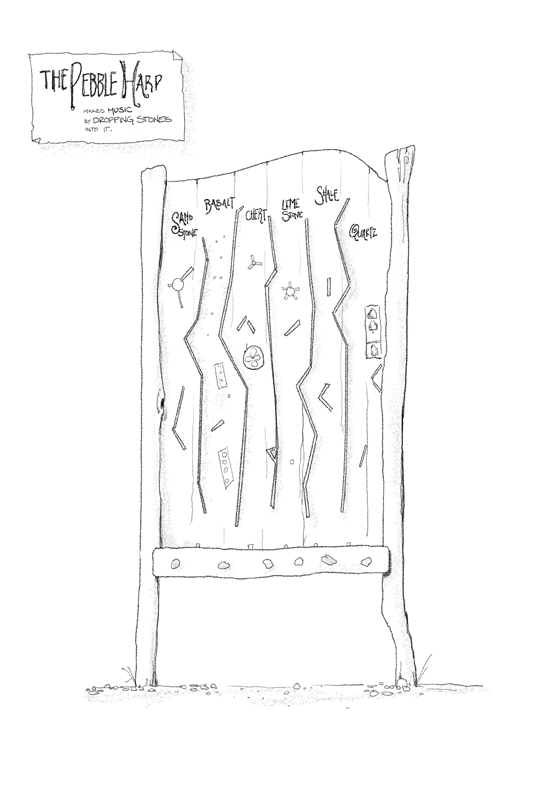

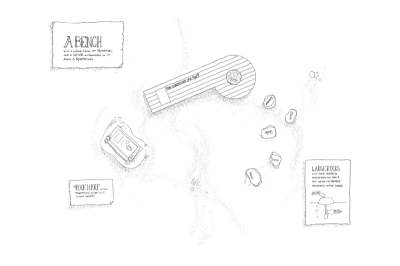

I had the great pleasure to meet with Marjie Ettinger, her husband Dick, and Rebecca Grill, Natural Areas Manager for The Park District of Highland Park over a year ago about this project. Marjie was interested in producing some kind of lasting installation about the multitude of rocks there. I was there to give it some shape: this is the early plan.

“The initial concept: a bench, a pebble harp, and a garden of giant beach stones, boulder-sized, with their names inscribed in them.”

It’s not every day one gets the opportunity to create art for a public venue, or get the help and support one needs to actually make it happen. I am extremely grateful to say that Marjie and Rebecca both fell in love with the idea and ran with it. The indefatigable Ms. Grill turned her considerable energies to making sure this idea came to fruition, recruiting geologist Charles Shabica to assist in picking out the five types of stones that would be set in the beach, and Eagle Scout candidate Duncan Holzhall (who brought a whole cadre of Boy Scouts along with him) to build the bench and the pebble harp.

Put the pebbles in the holes at the top and listen to them travel to the bin below. It’s good music.

The rocks were bought, and had their names carved into them, by the good folks at Schwake Stone, Brick, and Fireplace Company.

Already here in these photos you can see that the installation is working its magic; people engage with the garden, embellishing it with their own particular touches.

One of the significant motivating ideas throughout this project was to leave an opening for curiosity and wonder. In this day and age, when most of us carry the internet around in our pocket, it felt significant to not over-explain what is going on here at the beach. The rocks are simply identified, without any further explanation; the bench and pebble harp merely add anchors and further opportunity to engage with the area, also without explanation. Anyone can look up the names of these rocks on their phone and be connected to a wealth of information about them–far more than we could ever print on museum-esque panels mounted on poles on the beach. But is the beach really the place one wants to be standing and reading about rocks, geology, glaciers and currents and tides that move these rocks around? Or is it a place for play, for wonder, for exploration?

My contention is that one should leave the reading and academic information for where it can be absorbed best: at home, looking at a computer screen or the pages of a book. While at the beach – let’s play.

I hope you get to take a visit up to the end of Ravine Drive and explore the newfound serenity and natural peace found there. It’s a beautiful area, and I’m proud to have helped bring its new vibe into the world.